Alexandros Koumoundouros ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ ΚΟΥΜΟΥΝΔΟΥΡΟΣ

Born 1815 in the Mani Died 1883, Athens

Section 4 , Number 843A

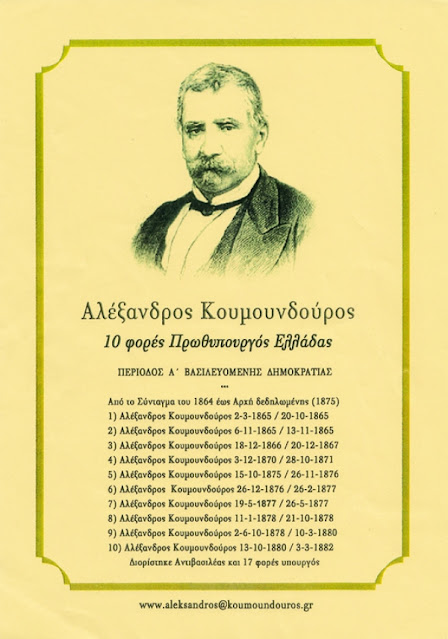

Maniot Alexandros Koumoundouros was born too late to fight in the Greek War of Independence but he made up for that by entering another battlefield: Greek politics. He was the target of assassins three times during his political career, incidents that would not have fazed a true Maniot because the Mani was a place where blood feuds, betrayals, and precarious alliances were a way of life. He survived and thrived almost continuously as a parliamentarian for 32 years and served an astounding ten times as Prime Minister, a record for a Greek politician. He held other posts as well, twice as Speaker of Parliament and 18 times as a minister, in the fields of economics, the interior, and education. Along the way he helped to strengthen and uphold the parliamentary system and significantly improved the lives of Greek Peasant farmers.

The Beginning

The Koumoundouros family has had a long history. They were forced out of Constantinople in 1453 along with other members of the Byzantine elite when it fell to the Ottomans. These displaced families scattered to just about everywhere - Epirus, Italy, Russia, and to the Mani, an arid, mountainous area in the south Peloponnese which had been home to bandits, outcasts and rebels since ancient times.

The Taygetus mountain range forms the backbone of the Mani.

There, a unique and hybrid culture had developed in which powerful clans cemented by family connections competed to build fortified towers. Each clan aimed to enlarge and consolidate its area at the expense of other clans. It was a hard scrabble existence with boundaries and alliances changing frequently. Banditry, piracy, and stints as soldiers for one war lord or another were their means of survival in the constant struggle to remain free and beyond the reach of the Ottomans. Many Mani clan leaders would become heroes during the War of Independence and a disproportionate number of them would later become politicians or members of the Greek armed forces in the new nation. Their heritage literally made them ‘fighting fit’.

The Koumoundourakis (1) clan settled in the northernmost part of the Outer Mani and by the mid 1700s, their influence stretched from the castle of Zarnata (today’s Kampos) north to what are now the southern suburbs of Kalamata (the area of Avia, Mikri Mantinea, and Selitsa). Their territory is shown on the map below:

The distance between Selitsa and the castle at Kampos is a mere 21 kilometres.

In 1760, Athanasios Koumoundourakis had control of Zarnata’s castle.

It was passed on to Panayiotis Koumoundourakis who became the Bey of the Mani in 1798. The Ottomans had been using local warlords as governors or Beys as early as 1670 because they had so little control over the area. It was a dangerous job and only a few died peacefully. The Ottomans did not trust them and quite frequently neither did their fellow Maniots. Panayiotis lasted until 1803 when the Ottomans arrested him. He died in a Constantinople jail.

This is the situation and mind set into which Alexandros Koumoundourakis was born in Selitsa in 1815.(2) It was an era when Maniot fathers like his own would announce the birth of a male in the family as an extra ‘gun’. An 1806 Traveller William Gell drew a sketch of Selitsa and wrote, The village of Selitsa affords an excellent idea of those inconveniences to which people submit for the sake of calling themselves free.

Selitsa, overlooked the narrow passage south to the Inner Mani. It became the site of a famous Maniote victory in 1826 when Alexandros would have been eleven or so. Ibrahim Pasha was attempting to enter the Mani from Kalamata. The defenders built a one kilometre stone defensive wall below Selitsa and, behind it, the Maniots held off Ibrahim’s superior force until Theodoros Kolokotronis could bring reinforcements. From above, the wall resembled a tree branch (verga in Greek). To commemorate the victory, the name of Selitsa was changed to Verga. That is why Koumoundouros’ birthplace is not found on any modern maps.

You can still visit the Koumoundouros tower house just outside of Kampos. It is hard to miss because a bust of Alexandros has been placed at its entrance.

1830 to 1882

When Greece finally gained its freedom, Alexandros was sent to high school in Nauplio, an educational opportunity hitherto denied to Peloponnesians under the Ottomans, and then went on to the newly established University of Athens to study law.

He interrupted his law studies in 1841 to volunteer in the failed Cretan Revolution against Ottoman rule and almost lost his life during the battle of Apokoronos near Chania. He then returned to Athens, becoming the secretary of Theodoros Grivas. In 1847, at the age of 32, he returned closer to home in Messenia, as the newly appointed deputy prosecutor of Kalamata, a position he held for three years. While there he married Aikaterini Mavromichali a member of the most famous Maniot clan of them all.(3) They had a son Konstantinos (1846 -1924) and a daughter who did not survive. After the death of his first wife, he would remarry and have a son, Spyridon and a daughter Olga.

He had his eye on a career in politics during the 1840s and in 1850 (4) was elected as a deputy representing Messenia. Apparently he shortened his name during this period, dropping the áki’ suffix.

Koumoundouros became a parliamentarian at a critical period in the development of parliamentary rule. Just 7 short years before his election, Bavarian King Othon had been ruling as an absolute monarch and the new constitution of 1844 was still weighted heavily in favour of the king. He could personally appoint the members of a 27 man Senate and appoint the justices of the realm. His legislative powers would raise eyebrows in any democracy today. Nor were there political parties in the way we understand the term today. Followers might coalesce behind a charismatic leader for a time and then sink into oblivion upon the death or defeat of their leader and then a new leader would emerge. It was a precarious system which promoted vicious political infighting, short term promises, and at the same time favoured the elite, the king, and, of course, the charismatic. The situation became slightly more even handed after the ousting of King Othon 1862 and the investiture of King George 1. The new constitution of 1864 abolished the senate and, on paper at least, the new king was more accountable to the nation.

By 1864, Koumoundouros had his own set of followers and probably an equally large number of enemies. A disgruntled Cretan veteran tried to kill him in front of the parliament buildings that year and who was actually behind that attempt was never fully established. In 1865 he decided to start his own political party, the Nationalist Party (Κόμμα Ἐθνικοφρόνων) and was elected Prime Minister for the first time that same year.

His Successes

Land Reform

Koumoundouros is remembered today because of the land reforms he instituted in 1871. When Greece became a nation in 1830, it was overwhelmingly rural and yet 70 percent of the land was owned by the state. This meant that over 120,000 Greek peasant farmers were virtually squatters on public lands. There was always talk about distributing this land but in some government quarters the view persisted that these lands might also be profitably sold to raise money for the cash strapped state. In 1871 Koumoundouros, as Prime Minister, changed the law, turning peasants into farmers on their own land. The criteria for possession was having lived on and used the land claimed for the previous 30 years. (The term for this in Greek is χρησικτησία and the law is still on the books today). This reform had the effect of giving a broad stratum of small farming landowners (about 50,000) a real stake and say in the democratic process. A positive by product of this agrarian reform was the reduction in banditry which was a plague during those years because so many of the destitute landless peasantry had turned to it in desperation.(5)

1881 Thessaly and the Area around Arta Join Greece

Land acquisition was, of course, the goal of the Great Idea - to encompass all ethnic Greeks into the new nation. It was never easy and success depended on the Big Powers and the astuteness of Greek politicians in pleading their cause behind the scenes. After a complicated series of negotiations in which Greece threatened war against the Ottomans, the Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire signed a treaty (The Convention of Constantinople, 24 May 1881) which finalized the new borders. The treaty was ratified in Greece on July 2 of that same year. This land transfer occurred when Koumoundouros was Prime Minister but he cannot take all of the credit. No Prime Minister was in power long enough during this period to be able to claim that any long term strategy was his alone.

The 1881 acquisition is in light blue

The End

Ironically, he was voted out of power in 1882 shortly after the acquisition of Thessaly; the newly enfranchised voters (mostly farmers!) had elected an opponent. As a result Koumoundouros resigned on March 3 of that year.

He died not long after on February 16, 1883 at his home in Plateia Ludwig just off Piraeus Street in downtown Athens(6). He was buried at public expense in the First Cemetery of Athens. In his honour, the square was renamed Plateia Koumoundourou.

Built in 1850, this neoclassical gem where Koumoundouros died first belonged to the Karatzas family. It was demolished in 1978.

Lake Koumoundourou on the road from Daphni to Elefsina is also named after Koumoundouros who had bought a great deal of the land in this area. There were two small lagoons, sacred in ancient times, and now one rather small and sad body of water:

Lake Koumoundourou

His party did not quite die with him because Theodoros Deligiannis carried on under its banner until he was assassinated on the steps of parliament in 1905. It was left to his more cosmopolitan and liberal political rival, Charilaos Trikoupis, to start a political party in 1872 based on a general set of principles rather than a leader’s popularity and the size of his following. Trikoupis was 17 years younger than Koumoundouros, a new generation really, and had been educated abroad as well as in Athens. Both his father and father-in-law had served as Greek Prime Ministers. His mindset was far more urbane and progressive than that of Koumoudouros who might be broadly said to have represented the old guard of Greece.(7) They became rivals and yet when Trikoupis was elected to parliament in 1865, the year Koumoundouros became Prime Minister, he recognized his ability and made him his Minister of Foreign affairs.

If you add up Koumoundouros’ stints as Prime Minister, it comes to just over 7 years during a 17 year period. Trying to be an effective leader under this revolving door system required strong nerves, persistence, talent, and, at times, the respect and support of rivals. During 32 years as a parliamentarian, Koumoundouros restored the strength of the Greek army, distributed national farms to landless farmers, and approved major construction work, including the first rail line in the Peloponnese from the town of Pyrgos to its port at Katakolo. It was a good beginning...

His portrait in the National History Museum on Stadiou Street

His family would carry on the political tradition. His sons Constantinos (1846-1924) and Spiridon (1858 – 1924) both became parliamentarians and ministers as did Olga’s son (1867 – 1928).

His Grave

Section 4, Number 483A

The Map

Footnotes

(1) The ‘aki’ suffix on surnames has apparently existed from Byzantine times. It was like ‘Mac’ in Scotland denoting ‘son of’. It naturally became a diminuative. The ‘aki’ suffix is today associated with Crete, but it was also prevalent in the Mani. Why a Koumoundourakis chose to become a Koumoundouros I do not know. Surnames in Greece were very fluid in the 19th century.

(2) There are various other spots in the northern part of the Outer Mani listed as his birthplace, but I opted for this one.

(3) Petrobey Mavromichalis was the last Bey of the Mani and the first from the Inner Mani. His tower complex has been renovated in Limeni and can be visited today

Petrobey Mavromichalis

The Mavromichalis were a large and influential clan; many were heroes of the War of Independence and many later entered politics. Petrobey himself became a decorated senator.

(4) I have read 1851 (in Veremis), 1853 and 1850.

(5) Banditry has an interesting history in Greece and has often been romanticised. It was endemic within the culture in the 19th century. As historian Ioannis Karavidas wrote, often one and the same family produced a farmer, a bishop, a head of the gendarmerie and an equally distinguished bandit

(6). I was sorry to see King Ludwig losing his square to Koumoundouros. Ludwig deserves to be commemorated.

(7) Trikoupis’ nickname was ‘the Englishman’ because of his urbanity and travels. Koumoundouros was a homeboy except a brief visit to Paris.

Some Sources http://www.flashmes.gr/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=598:aleksandros-koumoundouros&Itemid=419 got by googling the house of Kou... This article is prepared by Mair

https://www.proquest.com/docview/1732527326

Greece the Modern Sequel by J. Koliopolis and T. Veremis

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου