Dimitrios Eginitis ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙΟΣ ΑΙΓΙΝΗΤΗΣ

Born 1862 in Athens Died 1934 in Athens

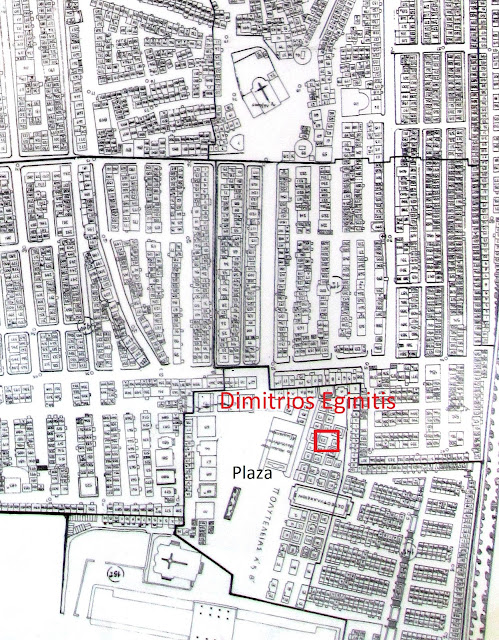

Plaza, Number 23

In an area of impressive funeral monuments, the one of Dimitrios Eginitis stands out because of its sheer size, classical elegance, and simplicity. Over the door, there is bas relief of a reclining angel resting on an hourglass, and a star emanating rays of light in the upper left hand corner, all well known funereal representations. An attractive narrow frieze above that would not be out of place on an early Christian tomb:

The Freize

But what caught my attention were the three words etched on the south side of the monument:

RELIGION ASTRONOMY EDUCATION

It seemed like an odd triad because, although astronomy and education go together and religion and education do go together in Greece, in today’s world astronomy and religion are not often a good fit. The combination became clearer as we investigated the life of Dimitrios Eginitis who was one of Greece’s most eminent astronomers and director of the National Observatory of Athens for 44 years.

During that period, he updated equipment, made stellar observations, founded observatories, and set up Greece’s Meteorological and Geodynamic (seismological) Departments under the aegis of the National Observatory of Athens. He was so well versed in French, German, and English, that he was often chosen to represent Greece at international conferences that had nothing to do with his specialization. And during a stint as Greece’s Minister of Education and Religion, he presided over the founding of the Academy of Athens, an august institution that had been a very long time in the making.

Eginitis was also instrumental in placing the entire country in the Eastern European time zone and, even more importantly, introducing the Gregorian Calendar to Greece. It was thanks to him that, in 1923, we lost 13 days in February (something I would be delighted to do more often) and, in doing so, synchronized Greece’s calendars with the rest of the world.

His Life

Demitrios was born in Athens on July 22nd, 1862 and at 17 graduated from the Varvakeion School (1). He then entered the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at the Philosophical School of Athens University where he obtained a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Mathematics in 1886. Thanks to a grant from the same University, he was able to study advanced astronomy and mathematics at the Sorbonne and by 1889 had secured a staff position at the Paris Observatory.

At this point he was travelling to various observatories, including in England and recording many observations using the meridian telescope. Like all academics, he published frequently, and gained international acclaim for his treatise on the stability of the solar system (Sur la Stabilité du Système Solaire).

Looked at in today’s post Einstein world, attempting to prove the stability of our solar system or the larger cosmos seems almost quaint, but a theory had been put forward that the planets, as they shifted on their axes, would inevitably move towards the sun and the certain destruction of Earth would be the end result. This was a disturbing proposition in an age of Faith. Eginitis proved with elegant mathematical certainty that this particular planetary catastrophe could not happen and his proof satisfied his peers at the time.

The beauty of science is not always in its accuracy, but in its ability to alter its proofs and theories as new hypotheses are presented and tested. More recent science has proven that the planets are, in fact, moving away from the sun at the speed of 1.5 cms a year because the sun’s nuclear fusion causes it to lose mass and therefore a tiny bit of its gravitational pull each year (2). I suspect a man of Eginitis’ calibre could have taken this in his stride were he alive today.

1890: Back Home to Greece and the Hill of the Nymphs

In 1889, Greece was in the awkward position of having an observatory on the Hill of the Nymphs opposite the Acropolis, but no one to direct it. This observatory, completed by architect Theophilos Hansen had been state of the art when it opened in 1846. Its construction was financed by Georgios Sinas, a wealthy banker and then Greece’s ambassador to Austria. He had wanted to make a contribution to the nascent Athens University and was advised of the need for an observatory.

Sinas’ Gift as it appeared in the beginning. Note how empty the area surrounding it is.

The Hill was far enough away from the city at that time to make an observatory feasible. Sinas, and later his son, Simon, paid the salary of the first directors, Georgios Vouris and of Julius Schmidt (3), an eminent German astronomer who was the first to create an accurate map of the moon.

He could keep a close eye on the acropolis from its eastern wing too.

When Schmidt died suddenly in 1884, the science of Astronomy in Greece was in deep trouble: no qualified astronomer and no money. Simon Sinas had died in 1876 and the Sinas bequest had finally been exhausted.

To its credit, small and poor as Greece was, the government was fully behind all educational ventures and Harilaos Trikoupis, the Greek Prime Minister got involved in the search for a new director. He had heard of Eginitis’ work, and made a direct appeal to the astronomer.

Eginitis hesitated and who can blame him? Greece’s financial problems were well known and Europe was a much more fertile field than Greece for an ambitious scientist. Still, Trikoupis promised Eginitis more instruments, money for new buildings, a staff to be chosen by himself and, as an added bonus, the same generous salary that Sinas had been paying Schmidt. Since the observatory was now under control of the government, Schmidt’s salary was well above the civil service pay scale. Therefore, Trikoupis’ last incentive to Eginitis required a special bill in Parliament. In a grand gesture, every single parliamentarian approved it. Imagine that happening today. There is something magical about this era and the hopes that it inspired.

So it happened that in 1890, the Athens Observatory got a new lease on life and a new 28 year old director.

Per Aspera ad Astra

Eginitis accomplished a great deal during his tenure in spite of the fact that Greece had declared bankruptcy in 1893 and he had to raise a good deal of the money himself for changes and additional equipment. (4) He added three buildings, one an observatory, just above the original, even buying the property needed for them out of his own pocket. It is amazing that, even in the 1890s, the hill was still considered suitable for celestial observations. Athens had clearer skies back then and not a lot of light pollution. We can thank him for the beautiful pine forest surrounding the observatory today. He ordered those trees planted.

It is a beautiful site and well worth a visit.

Eginitis bought specialized telescopes and other necessary equipment to modernize the facilities and enlarged the scope of the observatory’s functions. In 1902 he proposed a bill to parliament to divide the Observatory into three departments: Astronomical, Meteorological and Geodynamic, divisions that exist to this day – all under the name of NOA (The National Observatory of Athens) as the triad came to be called. EMY, the meteorological department was expanded to cover the entire country and its advice to farmers is still a valuable part of the national news.

The Times They are A’changing...

Eginitis was also instrumental in the country joining the rest of the world by accepting the Gregorian Calendar as opposed to the Julian which had been used in Greece since 45 BC. The Julian Calendar had itself had been an effort to synchronize an even earlier calendar with the earth’s yearly rotation around the sun; those all important spring and fall equinoxes and summer and winter solstices had to be kept in their proper places. The Julian calendars had been losing almost one entire day every 100 years. By the 1500s, it was out of alignment by 10 days. The Gregorian calendar dropped those 10 days in 1582 and fiddled with the leap years to keep things in alignment.

Not everyone liked the Gregorian changes, especially as they had been put forward by a Pope in a Papal Bull (Gregory XIII). It would take over 300 years before it was accepted worldwide for secular purposes. In 1923, Greece was the last holdout in Europe (5), so tardy, in fact, that it had to lop off 13 days rather than 10 in order to join the rest of Europe and the world.

Pope Gregory’s Papal Bull, published in 1582, Protestants didn’t like it any more than the Orthodox Church – at first.

One aspect of coupling Education and Religion under one ministry as Greece rather surprisingly does, is that it tends to make educators think about the Church’s reaction to educational choices. This is a far trickier brief today but, in Eginitis’ time, such sensitivities were expected and he did not disappoint. His understanding of the Church’s difficulty in accepting the reform of the new civil calendar actually won him accolades from the Orthodox Patriarch.

The same legislation brought Greece into the international system of weights and measures (the metric system). Here Greece was ahead of the United States and Great Britain.

Eginitis and the Athens Academy

The Athens Academy had a building long before it became an institutional reality in 1926. The Sinas family were, once again, the financial backers. Simon Sinas provided the money for the building that many consider to be the most beautiful neoclassical building in Athens.

The academy is one of the triad of Neoclassical buildings on Panepistimiou Street in Athens

The idea of an academy to promote the Sciences, Humanities, and Fine Arts had been around even during the Greek Revolution and had later been promoted by Greek intellectuals like Alexandros Rizos- Rangavis. The name was, of course, a reference to Plato’s famous academy. Those in favour of such an institution saw it as important for Greek national and educational aspirations as well as an important link between the present and Greece’s illustrious past.

But somehow, it never happened. Then in 1919, at the Paris Peace conference after the First World War, Greece realized that it was going to be excluded from the International Union of Academies, something that progressive Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos did not want to happen. He immediately asked Demitrios Eginitis to draw up a constitution for an Academy.

The Smyrna debacle intervened and it was not until 1926, under the government of Theodoros Pangalos, that a constitutional decree led to the actual founding of the Academy. At that time, Eginitis was again Minister of Education and Religion. Although he did not hold these ministerial posts for any great length of time, he did hold them when important matters arose and was thus able to influence change.

The Academy Interior has all the gravitas and grandeur of a basilica.

The Athens Academy has given and continues to give Greek scholars status both at home and abroad and supports scientific research, finances publications, and grants scholarships and awards.

In Sum

Eginitis died in 1934 at the age of 72. He left a legacy of achievements in the field of astronomy that other Greek astronomers have been able to build on. Now the European Union and European universities and institutions have replaced the Sinas family as partners and investors. Greece now has 6 observatories, the latest being the Aristarchos telescope on Mount Helmos in the Peloponnese where the air is a lot clearer and the nights a lot darker than in Athens. It is quite a landmark and can be seen from various vantage points both east and west of the mountain.

Its 2.3 metre telescope is named after the ancient Greek astronomer from Samos who was the first to place the sun, not the earth, at the centre of the known universe.

Eginitis was lucky that his career coincided with that of progressives like Harilaos Tricoupis and Eleftherios Venizelos. It enabled him to make the contributions that he did. But, it is to people like Eginitis and the Sinas family that we in Greece should be grateful for today, not just for their talents, but for their firm belief in the ability of Greece to make a real contribution to science and the arts.

Eginitis in the garden of the Observatory

The Map

Footnotes

(1 ) The original school was founded in 1860 and was opposite the central Market of Athens.

(2) For a fascinating article on this yearly slippage see https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2019/01/03/earth-is-drifting-away-from-the-sun-and-so-are-all-the-planets/?sh=1e7a2f596f7d

(3) You can find all about Schmidt on this blog: http://athensfirstcemeteryinenglish.blogspot.com/2017/12/johann-friedrich-julius-schmidt.html He is buried in the First in the Protestant section. For the National Observatory museum see:

https://www.ignant.com/2018/04/13/seeing-stars-in-athens-a-visit-to-the-national-observatory/

(4) Here is where connections counted; Eginitis called on all the usual suspects, including Andreas Syngros, and many came up with the needed cash

(5) Turkey did not accept the Gregorian calendar until 1927. Many Greek monks, still do not accept it, hence their name: the Old Calendarists.

Sources

See: Demitrios Eginitis: Restorer of the Athens Observatory at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/2007JAHH...10..123T . If you are technically minded, they list his acquisition of various machinery and telescopes.

For the Athens Academy see; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_of_Athens_(modern)

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου