Natalia Mela ΝΑΤΑΛΙΑ ΜΕΛΑ

Born July 10, 1923 Died April 24, 2019

Sculptor Extraordinaire

I was first introduced to the work of Natalia Mela through research on her husband, architect Aris Constantinidis. Fascinating as his life and career were, Natalia’s life and development as an artist is even more arresting – no easy feat - and not just because she was born into two of modern Greece’s famous families, but because she developed as an artistic force during an era which saw a dictatorship, a world war, a foreign occupation and a civil war occur, all during her most formative years.

She was a rebel from the get go. She enrolled in the School of Fine Arts at the age of 19 knowing full well that her family would object, joined the communist party briefly during the German occupation and chose to begin young adulthood living a bohemian life in a circle which boasted some of the greatest future artists of her generation.(1)

She was not born poor – far from it. She grew up in the lap of luxury and might have been expected to live the life of other girls of her class: ease, facility in languages and whatever other talents it took to become a decoration and helpmate to a husband. Her life is an interesting study in the difficult choices facing so many young people of intelligence and drive during those years when the country was both internally polarized and under foreign threat.

She began her artistic career as a sculptor in clay and marble, a field which has a distinguished history in modern Greece and in which many Greek sculptors have excelled. Then, in 1960 she moved into a practice hitherto uncharted by Greek women: metal.

And the results were stunning:

At 90, when welding became difficult, she switched from metal to paper, creating new and intricate work.

If the saying that artists are born and not made is true, then Natalia Mela may be all the proof we need.

Her Life

Natalia was born in 1923 in Kifissia into a famous family. Her grandfather, Pavlos Melas, an army officer, was killed in 1904 by an Ottoman sniper’s bullet while fighting in Macedonia as an irregular recruit. His death shocked the nation and he instantly joined the pantheon of the Greek heroes of the War of Independence, but this time as a hero in their struggle to add Macedonia to the Greek state. (2) His death left his wife Natalia Dragoumi-Mela a young widow with two young children (daughter Zoe and a son, ten year old Michalis). Her own family had long been part of the Athenian elite. Her father, Stephanos Dragoumis, had been prime minister, and her brother Ion Dragoumis a rising diplomat and writer had been killed by political rivals in 1920 and became a martyr as well.(3)

Michalis and Zoe Melas with their famous father

Growing up, Natalia’s father, Michalis, must have felt the full weight of his father’s legend. Much would have been expected of him. Not surprisingly, he attended the Hellenic Military Academy, his father’s alma mater and graduated in time to serve in the Balkan wars and World War One. He married Alexandra Pesmazoglou from another elite family and a very wealthy one. Her father founded the Bank of Greece. The stupendous grave monument of the Pesmazoglou family still dominates the entrance area to the First Cemetery.

Sculpted to impress by Francesco Jerace

This, then, was the privileged background into which Natalia made her appearance in 1923. As a child she benefited immensely from these connections. She would recall the idyllic years of her childhood in Kifissia: the wonderful family garden and the pet deer that her father had brought home alive from a hunting trip to entertain his children.

Natalia would later say that her family connections became a burden. Her family were confirmed royalists, firmly ensconced in the elite of Athens, and conservative with a capital C. It is perhaps not surprising that she rebelled, especially given what was happening in Greece in the 1930s. The Metaxas dictatorship had begun in 1936 when Natalia was 13. It was the culmination of bitter political infighting. Its fascist overtones and anti-communist stance may have helped trains to run on time and shored up the ruling class, but the implications of a regime which censored the press while requiring all youth to join EON, a youth movement modelled on Hitler Youth, had to have had a profound effect on a sensitive teenager.

Young members of EON. Metaxas did not mind being called a fascist.

Where this may have lead on its own is a moot point because the dictatorship ended abruptly on April 1941, when the Germans invaded Athens and the king along with most leading politicians abruptly abandoned the country to its fate as they set up a government in exile.

Natalia was 17.

I finished (secondary) school at the outbreak of the war. I had started to be curious about many things, politics in particular and became firmly opposed to my parents.... I wanted to be a child of the people. (4)

In 1942, unhappy with her studies in Law School, Natalia entered the Athens School of Fine Arts. One of her teachers was the great sculptor Michalis Tombros. The only serious resistance movement in the early months of the German occupation was the leftist EAM (the National Liberation Front). In early 1943 along with many in her circle, Natalia joined EPON, the youth movement of EAM. It was a short step from that affiliation to join the communist party itself. This she did, apparently proving her commitment by spitting on religious icons at the Kaisariani monastery.

Thinking about these juxtapositions is breathtaking. It is hard to imagine a step anyone could have taken in those dark years that did not involve a compromise: to go to a state school under a quisling Greek government, to join a resistance movement which had members who had been previously jailed as outlaws, to find ways to survive the terrible winter of starvation in 1942, and to be loyal - to whom?

A fellow student in her circle, Kitsos Maltezos had also joined the communist party. He was an important recruit because he was the great great grandson and last male descendent of Ioannis Makrigiannis, the hero of the War of Independence.

His recruitment was a propaganda coup. In fact, the flirtation of so many young people of the Athenian elite with the Party was one that EAM wanted to encourage because they, through their family connections, gave them entree to many of the philanthropic organizations that had been set up in Athens. Strange times.

Certainly not all who joined EAM were communists, far from it. But it is not hard to see its appeal to idealistic youngsters. But the KKE party structure backing EAM was also rigid, unforgiving, and cruel. Kitsos came to see this and had a change of heart. He decided to walk away. That was anathema. The party ideologues could not accept an apostate. He was tried in absentia and sentenced to death, a sentence which was carried out by four men in front of the statue of Byron on Amalias Avenue on Feb 1, 1944. Even worse, his murderer was a former friend, himself a member of a prominent family in Athens. The murder shocked Athens and would have served as a frightening warning to others who contemplated leaving the Party. (5) Natalia would later say that his death marked the end of her flirtation with communism. In later life, she would refer to this period as a mistake.

1945-50

The period between 1945 and 1950 was an active one for artists like Natalia. You might almost wonder if art allowed a kind of escape, a safe zone for young people caught in the social cross fire of the times. There is a wonderful picture of Natalia and her friend painted by Giannis Morales in 1946:

This work is in the National Gallery in Athens

She is holding a chisel, with other tools of the sculptor’s trade in the lower left hand corner. The pose is reminiscent of the famous Egyptian fayem portraits. That full frontal and cool gaze seems the perfect way to render her during this time in her life: determined and somehow defiant – or so it seems to me

In 1949 Natalie became a member of Armos (Αρμός) a group founded by Giannis Morales who had begun teaching at the Athens School of Fine Arts in 1947. It included luminaries such as painters Nikos Hatzikyriakos Ghikas, Giannis Tsarouchis and Nellie Andrikopoulou, with sculptors including Klearchos Loukopoulos and ‘Buba’ Lymberaki who is the other young woman depicted in Two Friends. The group’s first exhibition was at the Athens Zappeion in 1950 before moving on to Thessaloniki.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman

1950 and On

1950 marked the beginning of a change in her personal life. Her father, who had become a colonel in the army and an aide de camp of King George and then King Paul, died. And in 1951, she married modernist architect Aris Constantinidis. Two children swiftly followed and the next ten years saw her concerned with raising them but also doing set designs for the Karolos Koun Theatre. Aris was a rising architectural star at the time and just beginning to fulfil his promise.

Natalia and Aris

By 1960, Natalia was ready for the next step. She enrolled in the welding course at the Skaramangas shipyard, determined to create new work in metal. In 1963 she and Aris built their summer home in Spetses according to his own design. All this while, they lived in Athens in an apartment building designed by Ernst Ziller at 4 Vas Sophias Street. Natalia may have been one of the last people to actually live in a building built by the great architect. She used the old garage and stables as her workshop. This property had been a gift from her mother, Alexandra Pesmazoglou during the 1940s.

The Ziller building in its entirety. By Natalia’s time, half of it had been demolished but her flat remained.

Wealth does have its perks. The building is opposite the Benaki museum and directly behind the National gardens in the centre of Athens.

The rest, as they say, is history. Natalia continued to create all during her long life. She had a soft spot for Spetses and donated a many of her works to a park there.

Natalia never gave up sculpting the human form. In fact, during her career, she was commissioned to create busts or statues of famous people (some were relatives or monuments commemorating them) including the one below of her grandfather Pavlos Melas which is now situated opposite the White Tower in Thessaloniki.(6)

She had many solo exhibitions in Greece and abroad in 1948, 65, 67, 75, and 87 just to name a few. In 2008, when she was 85, the Benaki museum presented a major retrospective of her work. In 2011 Natalia received the Fine Arts Award from the Academy of Athens.

There was almost nothing she could not turn her hand to, from painting to collage, to marble and metal. But one aspect of her art intrigues me: those paper sculptures created during her old age. They are marvellous. In an interview with Diana Farr Louis in 1912, when asked about her latest medium she responded: What else would I do? I’d be bored with myself if I didn’t.

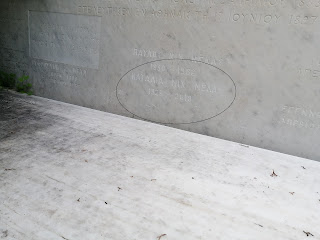

Natalia Mela died in 2019 and is buried in a Melas family plot in the First Cemetery.

Section One, Number 383

Although she apparently wore her husband’s wedding ring along with her own after his suicide at the age of 80, she is buried in a Melas grave not far from her husband’s in Section One, Number 482.

The Map

Footnotes

(1).The list is a long one including Nellie Andrikopoulou, Buba Lymberaki, Nikos Koundouros, Lena Tsouchlou, Giannis Morales, Giannis Tsarouchis, Dimitris Pikionis, Nikos Egonopoulos, Andreas Embeirikos, Odysseos Elytis and on and on.

(2) The actual death of Pavlos Melas was a drawn out affair during which his words were recorded by his friends and related to the world. The very fact that he was an irregular helped create his legend. Ever since Klefts and Souliots and war lords like Kolokotronos and Mavromichaelis, Greeks have had a fondness for the ‘outlaw’ patriot.

(3) Greece has had a shocking number of political and ideological martyrs during its modern history.

(4) See http:/www.nataliamela.gr/WebsiteEn/bio andrikopoulou.php

(5) A great deal has been written about this incident. Andre Gerolymatos in his book An International Civil War devotes two pages to the story, again stressing the trend among the young elite to espouse the communist cause and also related that the family of one of the murderers preferred that he be arrested by the Gestapo and shot (which he was) for having an illegal firearm rather than having his connection with the communist party become known. One friend referred to her as a royalistcommunist because her family were such well known royalists. Such contradictions almost seem normal for Greece at times.

(6) She created a bust of Georgos Pesmazoglou at the National Bank in 1951, the monument of the Fallen Soldier, Zagoria, in 1964, a statue of actress Givelli for the Athens Cultural Centre in 1994, and the statue of Pavlos Melas erected in Thessaloniki in 1994.